From novice to master: The existential paradox of experiential learning

The Lived Experience of a Novice

When I began teaching, I thought I knew what I was doing. It did not take long before I realised that I did not know what I was doing. Doubt, self-doubt, and anxiety began to settle in. Luckily, I had a supervisor who put the journey into perspective by telling me that I was a novice and as such could not expect to know what I was doing. The thing, she said, is to be able to work within the existential psychological dimensions of not knowing what I was doing. She encouraged me to see and reframe my uncertainty of not knowing as the basis for the emergence of curiosity, wonder and re-searching.

Calling myself a novice provided me with a framework within which to set expectations that were appropriate for being a novice. I did not expect to be an expert and so did not need to feel the pressure to perform straight away. I did not get lost in the ‘imposter syndrome’ that so many novices suffer from. Although being challenged by teaching, I could see the challenges as opportunities for developing an embodied understanding of teaching. I needed to learn to listen to the voice of being lost.

My experience of uncertainty in not realising that I was a novice is not unique to me. As Daniel Mackler, a psychologist writing of his own experience as a novice says:

“[University education] also taught me to feel that I should know the answers, that I should be a fountain of wisdom and maturity and confidence. Well, what about all those times when I had no clue what to do or say? This was especially difficult when people had super-serious problems that had no simple solutions, especially given the surrounding, broken mental health climate. How was I, with all my training … supposed to be an expert when I had no clue what to do?”

In this quote, we see that not only is the novice consumed by an anxiety but also that this anxiety is reinforced by what he believes to be the expectations placed on him by the university. This is the perception that the university believes that he should know all the answers. In other words, he is going into the unknown and expecting himself to be an expert at the same time. This is a contradictory state of mind overwhelmed by stress and tension. We also sense the terror of feeling stuck in a state of having “no clue.” It would be helpful if there could be a transformation in his attitude towards not “having a clue” that would allow him to see it as an existential psychological opportunity for on-the-job learning.

It is often said that we learn through experience, but what seems to happen is that we struggle to give ourselves the opportunity to learn from experience. We often feel the pressure of needing to be an expert from the get-go and thus get lost in the so-called “imposter syndrome.” As Jessica Price in an article called “Insights from an Early Career Psychologists” says of herself as a novice:

“I ran my fingers against the desk, looking around the room, trying to remember my training, reading about effective intake interviews, but nothing was sinking in. All my brain could think was ‘oh god, oh god, oh god – are they going to know I’m an imposter? That I’m not supposed to be here?”

It is important to note that these feelings of being lost are not unique to early career professionals but are experienced with the same degree of shame and perplexity by senior novice leaders who feel their very sense of self is at stake in the uncertainty of the unknown. A novice head teacher in a research study says:

“I DON’T think there was any one thing that made me feel that I was a headteacher, but for the first couple of terms I really felt I that I wasn’t me. … I was somebody else who was being forced to play a part in a play, and I didn’t have the script.” (1)

In this last quote we see a sense of being lost, of having no embodied script or map of the journey. We also see how the lived experience of a novice can lead to a loss of a sense of self, the feeling that she was not herself.

What framework will enable novices to work through uncertainty, transforming it into the excitement of learning?

The Existential Paradox of Experiential Learning

These disruptive emotions are not just anomalies but rather are an intrinsic part of the experiential journey towards skill development and becoming a professional. Novice professionals tend to think that they alone experience self-doubt and uncertainty. They do not tend to see that many others go through periods of self-questioning and anxiety. Professional development courses tend not to provide novices with the understanding that such disruptive emotions are an intrinsic part of being a novice. Instead of normalizing these experiences, there is a tendency to see such experiences in a negative light, as signs of not coping and thus of something wrong. Normalizing these experiences means seeing them not just as obstacles to skill development but as opportunities to tune into the emotional wisdom of the profession. They are educational opportunities.

The novice professional is in the grips of what I have come to call “the existential paradox of experiential learning.” On the one hand, novice professionals need the skills of a profession to engage in the lived experience of the profession, but, on the other hand, they only develop those skills by participating in the practices of their profession. This point is made by Linda Hill, a very well-respected researcher in the field of management, who, writing in the context of management, says that the managers “had to act as managers before they understood what that role was. Only by acting would they know what their new [role] entailed.” Continuing her point, she says that novice managers are “trying to learn a role whose meaning and importance they could not grasp.” (2) It was only by immersing themselves in the role that they developed an understanding of the role.

We need the skills of a role to perform that role, but we only internalise those skills in the context of performing the role. Hill describes the experience of being in the existential paradox of experiential learning as “emotionally unsettling.” (2) The same emotionally unsettling paradox is at work in learning to drive a car. That is, one needs the skills of driving in order to drive but it is only through driving that we internalise the skills of driving. Similarly, we need the skills of cycling to cycle but we only inhabit those skills by cycling. This point applies to all skill development: we inhabit the skills and become artists by immersing ourselves in the world of art, we become plumbers, doctors, lawyers, teachers, psychologists, and electricians by immersing ourselves in our roles. As we do so, we develop our way of being in these professions, and we start to develop the felt sense of the skill.

The virtues of being a professional are internalised in the same way: we become wise through the ways in which we work through the experience of the unknown. We develop courage through embracing rather than refusing our fears. Leadership is developed through leading. Writing in the context of organisational leadership, Edger Schein, a leading researcher in organisational behaviour, exemplifies this point:

“Until one actually feels the responsibility of committing large sums of money, of hiring and firing people, of saying no to a valued subordinate, one cannot tell whether one will be able to [embrace it].” (2)

Uncertainty, confusion, threats to sense of self, doubt and self-doubt seem to be integral parts of being a novice. Of course, this does not mean that there is no excitement in being a novice. But it requires the emotional acceptance of a learner’s mindset to feel the learning opportunities present in being a novice.

Existential Anxiety, Leaping and Taking Risks

The novice is in the existentially challenging paradox of the unfamiliar and unknown. Existential anxiety is that anxiety which arises when we do not have the familiar routines, conventions, or habits for performing a task that we need to perform, but we need to have the skills to perform it in the first place. In existential anxiety we have nothing – no-rules, no habits – upon which to rely. Everything is unfamiliar, yet we need to move forward. And it is only by moving forward that the unfamiliar will become familiar, that we will develop the felt sense of skills and routines for doing things.

Textbook knowledge or following manuals is not going to help the novice develop a felt sense of their field or to internalise their skills of wise practice. And the novice cannot “think” themselves into the felt sense of a profession. Just because they may understand a skill intellectually does not mean they have a felt sense for performing the role.

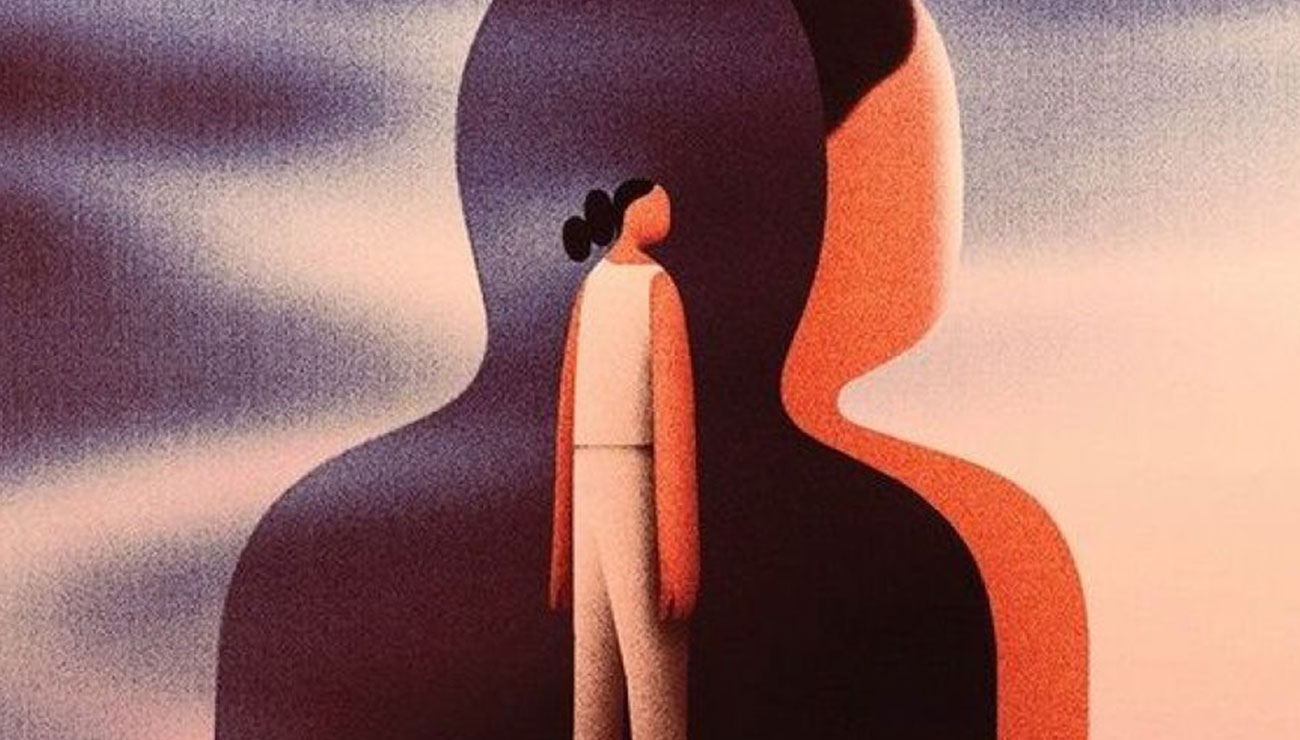

The novice is faced with the “existential abyss.” There is nothing that they can hold onto in inhabiting the skills that will only be inhabited by taking a leap across the abyss into the felt sense of the skills and role. They are confronted by an existential choice: “to be or not to be” in the role.

This question cannot be answered by rational thinking. It involves an existential choice: to venture into the anxiety of the unfamiliar or withdraw in the safety of the known and familiar. As Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard said: “To venture causes anxiety, but not to venture is to lose oneself.” (3)

The leap across the abyss involves an existential risk. A novice clinician has described the risks that she needed to take in inhabiting her professional skills:

“Every day was a challenge, and while not an easy one, I loved it. It was extremely stressful, because often I wasn’t quite sure what to do or what to say or how to behave. I was constantly taking risks — emotional risks — and really expanding sides of myself. This high degree of testing not only engaged me at a deeply personal level, but also really improved me as a clinician. That was gratifying.”

As indicated in the quotation above, taking risks not only is full of anxiety but also contains much excitement. The novice clinician above said that she loved the existential learning experience she was in. Adventures are exciting because they disclose the possibility of the new—new skills, ways of doing things, routines and ways of being. These are not mutually exclusive but occur simultaneously. The simultaneous experience of anxiety and excitement will be called “anxietment.” It is this mixture which confronts the novice in leaping across the abyss.

Taking these existential risks, embracing the unknown through a leap opens the world for new skills, identities, and ways of being a professional. Refusing to venture leads to the despair and frustration of career derailment at worst or mediocrity at best. Embracing the leap allows for the development of confidence and competence. Refusing the leap, expresses itself as feelings of low self-worth, self-doubt and a sense of not being good enough.

The well-known German philosopher Martin Heidegger says that the mood of resolve is required of the novice in leaping. Being resolute involves accepting and embracing the anxiety of the unknown and unfamiliar in projecting oneself into the new role. Rather than running in fright from such anxiety, “lean” into it. Feel it run through you. A poet coming out of the romantic tradition, Rainer Maria Rilke expresses the mood of existential anxiety. Writing to a novice poet who feels quite unsure of himself as a novice poet, Rilke tells him to: “… have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language”.(4)

The challenge to be resolute is crucial to skill development not only for the poet but for all skill development. Embracing doubt and excitement are essential to leaping onto the bicycle for the first time. Developing the skills of being a doctor, electrician, salesman, teacher require the resolve of embracing the uncertainty of the unfamiliar and unknown. Paraphrasing Shakespeare, to leap or not to leap is the question. Embracing the uncertainty of the leap allows for professional development. Refusing the leap gets in the way of developing the felt sense of the skills. It gets in the way of internalising the skills of professional development. The leap is crucial to the development of professional identity. Refusing the leap creates an unfulfilled sense of self.

From novice to emotional wisdom

Dreyfus and Dreyfus, (5) well-known scholars of the philosopher Heidegger, have offered a model of skill development that consists of five levels: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and mastery. I am not going to go through all five stages but want to discuss the final stage, mastery.

In the stage of mastery, professionals know exactly what to do without having to think about it. They have developed an intuitive know how of their profession. This is a stage in which a professional can intuitively coordinate the whole and parts of a role. In my capacity as a management coach, one of my clients exemplifies this when he compares management skill mastery to the mastery involved in driving a car:

“You sort of learn over time and you realise that becoming a manager is kind of like driving a car. When you are driving for the first time, you are worried about the right acceleration, and the gear shift, and the signs on the road, and the horn, and the instructor, you know, it’s too confusing! But when you have driven the car for a few years, you realise that it’s automatic and you’re also learning to text (on the) phone while driving.”

While not condoning the activity of texting while driving, the point is that skill mastery is a complex activity in that it does not involve simple incremental learning but learning to balance many functions simultaneously. It is not that a novice or new learner can learn the balance of driving by first pushing the break ten times so as to practice it and subsequently the accelerator another ten practice turns, clutch and steering wheel, while then practicing a sense of making sure that one is centred in one’s lane and after that looking ahead. Balance is not the sum of the parts. Learning the felt sense of balance of driving a car is being able to do all of these activities simultaneously whilst on the move. There is a simultaneous going forward and backward until what I shall, following Heidegger, call a “familiar sense” or “felt sense” of the whole develops and a familiar sense of the whole allows each of the parts to stand in relationship to one another.

Mastery is about an intuitive sense of balance in executing skills. Aristotle puts the complexity of balance together in his definition of practical wisdom which is summarised by Hubert Dreyfus. Practical wisdom, he says, is to “straightway do the appropriate thing at the appropriate time in the appropriate way.”

The example that Aristotle gives is the mood of anger. He defines the emotional wisdom of anger in the following way:

“Anybody can become angry – that is easy; but to be angry with the right person, and to the right degree, and at the right time, and for the right purpose, and in the right way. That is not within everybody’s power and is not easy.” (6)

Based on the quotation above, it can be said that emotional wisdom, from an Aristotelian perspective, is the ability to be attuned to the right task or person, to the right degree, at the right time, for the right purpose and in the right way. Emotional wisdom is distinguished from emotional intelligence in that the former is contextual whereas the latter seems to be defined in relation to the self. However, that is a theme for another article.

Pierre Bourdieu, a highly influential French sociologist and philosopher, describes the virtuosity of such mastery:

“Only a virtuoso with a perfect command of his “art of living” can play on all the resources inherent in the ambiguities and uncertainties of behavior and situation in order to produce the actions appropriate to each case, to do that of which people will say: “There was nothing else to be done,” and do it the right way.” (7)

The role of the therapist and coach in facilitating the transition from novice to mastery

The question is: How we can facilitate professionals in the transition from being a novice to mastery of the skills and way of being of a profession. This is not something that can be done by formal education, which is conducted in abstraction from the contingencies of the workplace. It requires a kind of leadership coaching or psychotherapy that can provide a “safe space” in which a novice can leap into the uncertainty of professional performance. Leadership coaches and therapists provide novices with a framework to lean into and to work through the unknown. In these contexts, the unknown is transformed from a paralysing terror into an opportunity to learn. Andrew Grove, former CEO of Intel writing in the context of skill development exhorts us to let chaos reign so that we can rein chaos in, and this is exactly the learning opportunity provided by coaches and therapists. (8) Through this process, therapists and coaches enable novices to bring out the best in themselves. The danger of not embracing the anxiety of the unknown, as was earlier emphasised, is career derailment.

Steven Segal